Intro

It had been a while since I last took the time to reverse a real malware sample from scratch.

To avoid getting rusty (and because it’s genuinely fun), I gave myself a simple challenge: grab a completely random malware sample and see how far I could go analyzing it.

Off to MalShare, random click, download a binary without knowing what I was getting into.

Spoiler: it wasn’t a crappy crack — it was a fairly ambitious stealer, with password theft, Discord tokens, encryption, and the usual toolkit.

Fingerprints

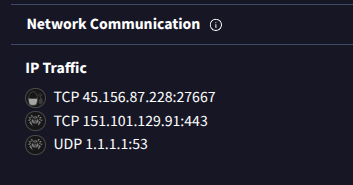

First data points:

1 | File: malware |

At the time this article is written, these identifiers are already known (VT, etc).

However, the IoCs (especially contacted IPs) do not fully match what I found 👀

First contact

Let’s open the sample with the best tool (the one and only :binja_love: ). And then:

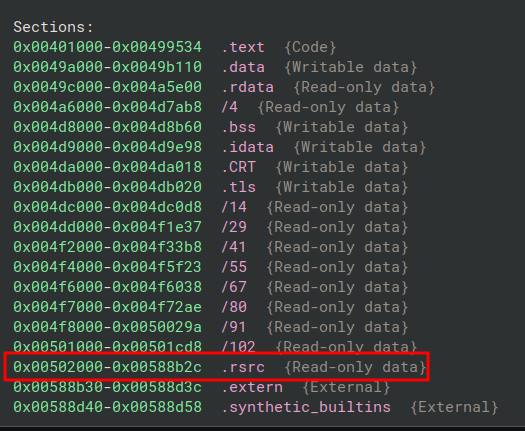

.text → 200 KB (Executable code)

.data → 50 KB (data, ok)

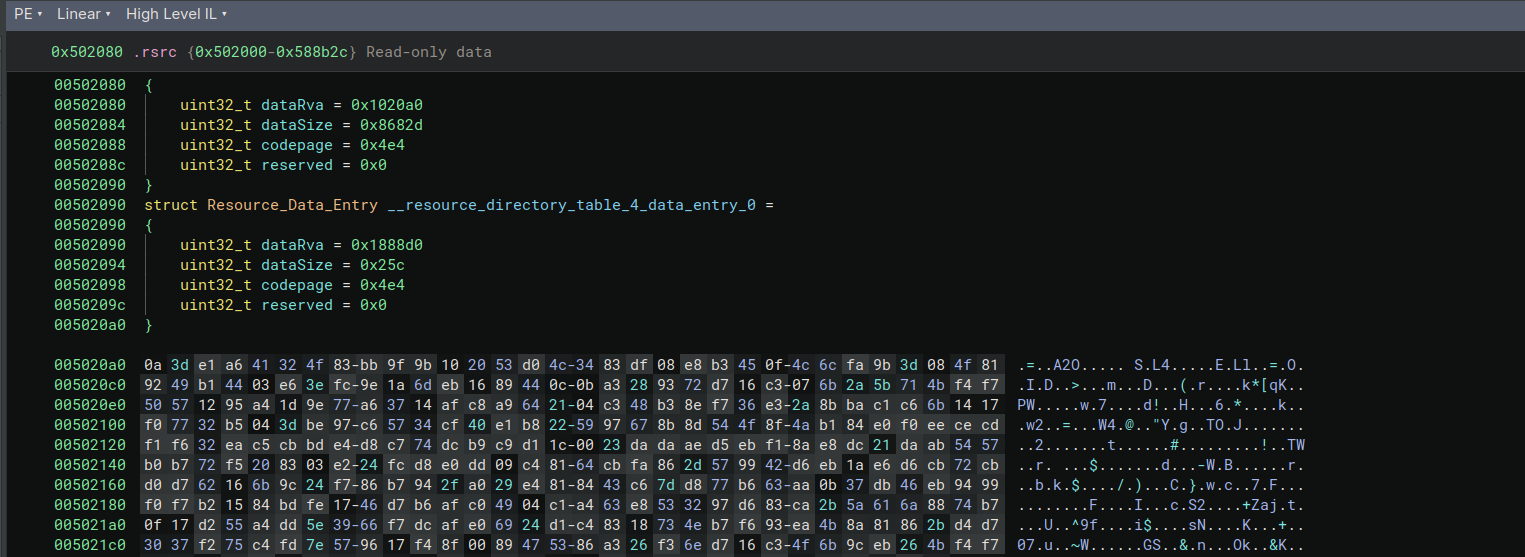

.rsrc → 539 KB WTF?!

539 KB of resources… In a 1.5 MB console executable… yeah, right.

For reference, .rsrc is supposed to contain legit stuff: icons, Windows dialogs, UI strings, etc. Normally just a few KB, rarely over 100 KB.

Here, we have half a megabyte of data. And looking more closely: no structured icons, no dialogs, no multilingual strings… Just a big binary blob with very high entropy (7.8/8.0).

Almost certainly encrypted.

Strings & Ciphers

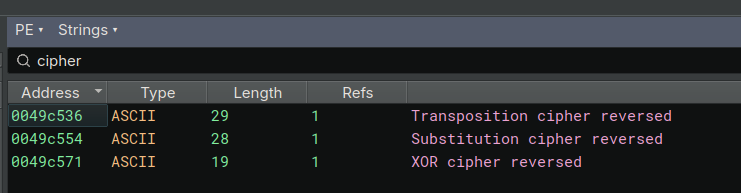

First step: look at the strings — we quickly stumble onto:

Jackpot !

1 | "XOR cipher reversed" |

Not subtle at all…

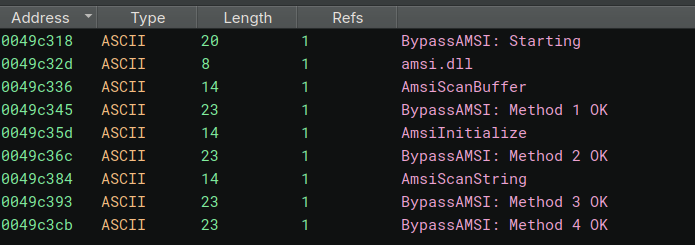

We also notice many anti-debug related strings, plus classic malware stuff (AMSI patch, sandbox detection, etc). The logging is very verbose — they probably forgot to remove debug messages…

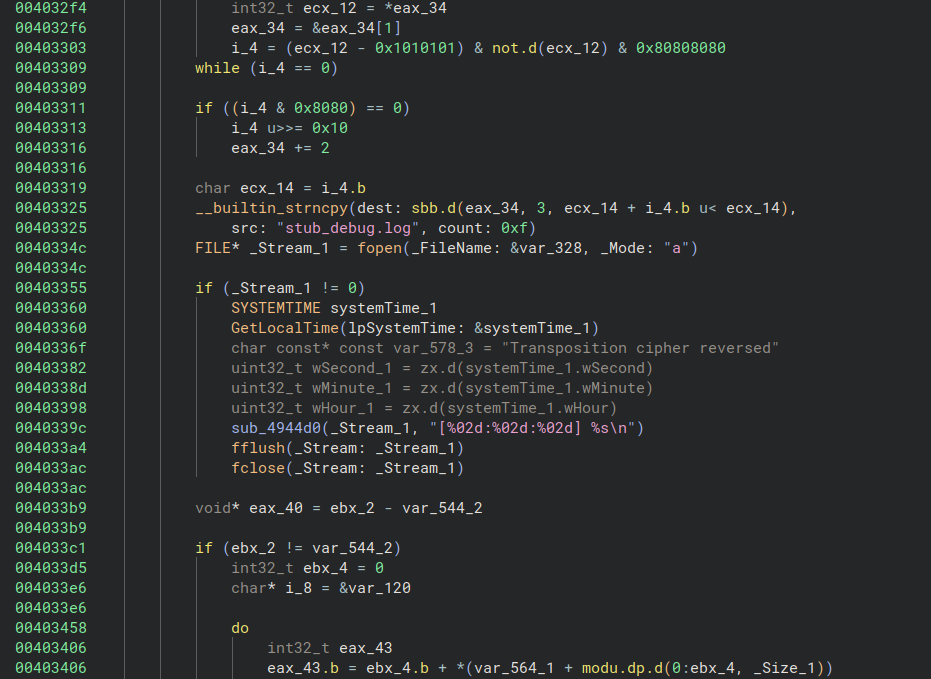

With the xrefs, we can identify the method that “decrypts” something:

This function is fairly large, with many memcpy/malloc, lots of loops, strongly suggesting a “decryption” routine.

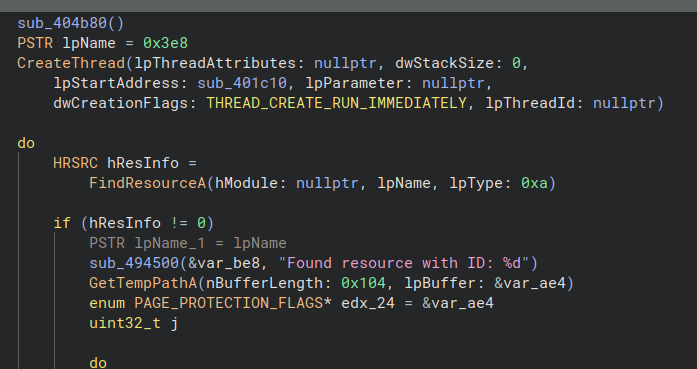

Looking at where it’s called, we see another heavy function that — surprise — fetches data from .rsrc before calling decryption…

Cleaning up all the AMSI, ETW, etc. patching calls, it looks like:

1 | ... |

Clearly, it scans resources for a specific one, checks sizes, decrypts it, and executes the output — classic.

Decrypt

Now we need to extract and decrypt the payload to understand the malware behavior.

According to the embedded debug strings, the algorithm is in 3 stages:

- Transposition cipher reversed

- Substitution cipher reversed

- XOR cipher reversed

Payload extraction

First, we extract the payload.

The dropper pulls resources of type 0xa.

Using debug strings and size checks, we can infer the header structure:

1 | "Header parsed - headerSize: %d, blockSize: %d, keySize: %d, encryptedSize: %d" |

There’s also a check:

1 | 004062fd if (_Size u<= 0x31) |

From this, we deduce a header like:

- headerSize : between 8 and 15 bytes

- blockSize : probably 16

- keySize : probably 32

The rest looks like key + encrypted data.

Looking inside .rsrc, we quickly find a blob matching the format (right after standard resource structs):

We also see buffers similar to:

1 | struct DataBuffer |

Then the 3 decryption steps start.

Transposition

This one is simple: data is processed in 16-byte blocks and each block is reversed.

1 | Input: [00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 0A 0B 0C 0D 0E 0F] [10 11 12 ...] |

Easy

Substitution

This part is trickier.

It uses a dynamic substitution table built per-byte using the key.

- Compute

base = (i + key[i % keySize]) % 256 - Build table:

table[j] = (base + j) % 256 - Find inverse:

find j such that table[j] == encrypted_byte - Replace byte with

j

It’s more obfuscation than encryption.

Thanks to debug strings, it was much easier to understand :D

As simple as a XOR

Final step: classic XOR loop using the 32‑byte key.

Let’s decrypt

Running all 3 steps on the extracted payload gives:

1 | def reverse_transposition(data, blockSize): |

We indeed get another binary!

1 | ghozt@maze:~/research/malware$ file output.exe |

.NET stealer

With ilspy we extract the C# code:

1 | ghozt@maze:~/research/malware$ ilspycmd output.exe -o ./decompiled_dotnet/ |

We quickly notice the strings are obfuscated.

Still, we can analyze the general behavior: credential theft, Discord token extraction, decrypting Chrome’s password store via DPAPI…

As for the strings, everything is AES‑encrypted with a lightly obfuscated key:

1 | public static class Strings |

There are 190 encrypted strings.

All use AES‑CBC, but with a twist: ciphertext is reversed before decryption.

AES keys themselves are XOR’d then Base64‑encoded.

Reproducing the algorithm gives:

1 | AES Key: OFhBENNkSFZaYyg2w6yQi5Mrqn7ypiPXDrim64w/FM0= |

And we can decrypt everything!

Targets and data theft

Browsers :

1 | Login Data → Credentials Chrome/Edge/Brave |

Messaging :

1 | discord\Local Storage\leveldb\ → Discord Tokens |

Crypto Wallets :

1 | wallet.dat → Bitcoin Core, Litecoin |

VPN :

1 | NordVPN\user.config |

Gaming & FTP :

1 | Steam\loginusers.vdf |

And the big one:

1 | net.tcp://185.172.128.70:3808 |

This is the C2 where all stolen data is sent using WCF (Windows Communication Foundation).

System recon

The malware also collects lots of system info:

1 | SELECT * FROM Win32_Processor -- CPU |

And detects security products:

1 | ROOT\SecurityCenter\AntivirusProduct |

Overview

With all strings decrypted, we can reconstruct the complete workflow:

Phase 1 : Recon

- System info (CPU, GPU, RAM, disks, OS)

- Security product detection

- VM/sandbox checks (QEMU, RDP)

- Running processes

- Installed software

- GeoIP via https://api.ip.sb/ip

Phase 2 : Data theft

- Browsers: credentials, cookies, autofill, credit cards

- Discord: tokens via LevelDB

- Telegram: tdata folder

- Wallets: crypto wallet files, extensions

- VPN: configs for NordVPN/ProtonVPN/OpenVPN

- FTP: FileZilla

- Gaming: Steam login data

Phase 3 : Exfiltration

- Compress stolen data

- Connect to C2: net.tcp://185.172.128.70:3808

- Send via WCF binary protocol

Persistance

One encrypted Base64 string decodes to another .NET executable, which is written into the Startup folder:

1 | using System; |

This is likely a dormant backdoor allowing later reattachment.

Conclusion

This sample appears to be a variant of Reline, a fork of RedLine Stealer that surfaced after the October 2024 takedown.

It features:

- Custom packer with simple ciphers (transposition + substitution + XOR)

- WCF exfiltration instead of SOAP/HTTP

- Debug strings left in

- Obfuscated .NET payload

IoCs Summary

1 | Dropper: |